A portrait of one of the most important living thinkers in the fields…

Judith Butler

- Description

- Reviews

- Citation

- Cataloging

- Transcript

If you are not affiliated with a college or university, and are interested in watching this film, please register as an individual and login to rent this film. Already registered? Login to rent this film.

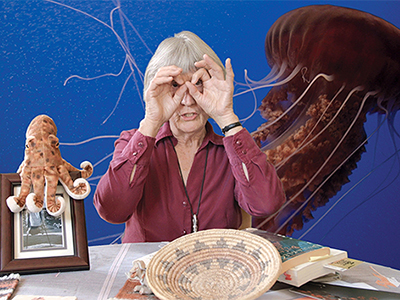

Author of the best-seller Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, Judith Butler (Maxine Elliot Professor in the Departments of Rhetoric and Comparative Literature at University of California, Berkeley) is one of the world's most important and influential contemporary thinkers in fields such as continental philosophy, literary theory, feminist and queer theory, and cultural politics.

JUDITH BUTLER: Philosophical Encounters of the Third Kind is an up-close and personal encounter with this educator and author. The film features interviews with Butler — including reminiscences of her formative childhood years, illustrated by family home movies, as a 'problem child' — shows her in classroom sessions in Berkeley and Paris, at public speaking engagements, and in discussion with Gender Studies professor Isabell Lorey.

Does gender = sexuality? How does the family define gender roles? What are the dangers when society coerces gender norms? What deep-seated social fears are unleashed by those who flout those prescribed roles? What is New Gender Politics? These are just a few of the topical issues explored in the film.

In the film, Butler covers a wide range of subjects, broaching not only controversial gender issues-including transsexuality and intersexuality-but also 20th century Jewish philosophy, AIDS activism, criticism of state power and violence, gay marriage, and anti-Zionism.

PHILOSOPHICAL ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, the first film profile on Judith Butler, will serve to popularize her insightful analysis of sexual identity and gender roles at a time when the cultural and political debate over these issues pervades American society.

'Important... The strength of this film lies in its ability to give viewers a flavor of Butler's thought without caricaturing that thought. The film pulls together diverse aspects of Butler's arguments that provide a sense of the way she wishes to reorient our thinking.'-Samuel A. Chambers, Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies

'An excellent introduction to the work and philosophy of a woman who has tired to avoid and often combat societal 'pigeon-holing' based on gender and sexuality... an excellent resource for classroom use... For librarians, philosophy, and women's studies instructors, JUDITH BUTLER should be considered a needed addition to their collections.'-Elizabeth Ross, River Walk Journal

'A warm and illuminating portrait that enables us to discover the personality and thought of this engaged intellectual.' Le Monde

'An essential figure on the American intellectual and political scene... [includes] truly revelatory examples of the liveliness of a theoretical reflection in direct touch with the contemporary world.' Télérama

'A sensitive and invigorating portrait [of] one of the most effervescent spirits of our time.' Les Inrockuptibles

'Illuminating...has much to say about feminist theory, identity, gay rights, AIDS activism, homosexuality, and Israel.' Booklist

Citation

Main credits

Buzareingues, Anne-Françoise de (film producer)

Zajdermann, Paule (film director)

Fassin, Éric (narrator)

Other credits

Edited by Michéle Loncol; camerman, Jean-Luc Cohen.

Distributor subjects

Critical Thinking; Cultural Studies; Gender Studies; Jewish Studies; Lesbian Studies; Literature; Philosophy; Philosophers; Rhetoric; Women's StudiesKeywords

« Judith Butler, philosophe en tout genre » de Paule Zajdermann

montage continuité 6 / 6 juillet/ 52’19

VO

10:00:00:00

Seq 1 Générique

Cartons sur fond noir avec inserts très courts d’archives butler enfant fête costumée

10:00:07:10

Off éric fassin :

Qu’est ce que c’est qu’un homme ? qu’est ce que c’est qu’une femme ? qu’est ce que c’est que la masculinité ? qu’est ce que c’est que la féminité ? qu’est ce que c’est que l’homo sexualité ? qu’est ce que c’est que l’hétérosexualité ? qu’est ce que c’est que tout ce qui n’entrerait pas dans le cadre de cette alternative ?

On est allé lire Judith Butler parce que c’est d’abord quelqu’un qui réfléchit sur l’identité et sur les normes…et sur une politique des normes qui ne soit pas fondée sur une identité stable, qui ne soit pas fondée sur une identité éternelle, qui ne présuppose pas une identité… ce que nous fournit l’œuvre de Judith Butler c’est des instruments pour réfléchir à cette évidence perdue des normes.

10:01:09:20

Seq 2 ITV JB Berkeley

I'm lesbian...gay, yes, I'm lesbian gay, but do I subscribe to everything the lesbian and gay movement says, do I always come out as a lesbian and gay person first? Before, say... I am a woman or before I am a Jew or before I am an American or a citizen or a philosopher? No, you know it's not the only identity. So, these are communities where one belongs and one does not belong. And it seems to me we travel, I travel.

Archives butler enfant

I was born in Cleveland, Ohio, into a Jewish family and my parents were very engaged in politics and debate and...

Photo

I was never very good in school. I was what they call a problem child, I was what they call a disciplinary problem and I would speak back to the teachers and I would not follow the rules. I would skip class. I did terrible things. And yet I was apparently smart in some way, but I didn't understand myself as smart, I understood myself as strategic. One had to get through, one had to find one's way in school and synagogue. And I didn't really like authority.

Photo

My mother was called into the principal's office, the principal who runs the school, when I was in 5th grade, I think, at, probably, the age of 11 and she was warned that I might become a criminal.

Photo

And at that point they told me that I couldn't go to the... to the school anymore, to the Jewish education program anymore, unless I.. I studied privately with the rabbi. So, this was, for me, terrific, because I loved the rabbi and, in fact, I skipped the class, my regular Hebrew class, in order to go into the sanctuary to listen to the rabbi speak. And the rabbi spoke about extraordinary things. He... His name was Daniel Silver and he wrote a book on Moses.

Photo

So when I was forced to have a tutorial with him, I was privately very happy. And he asked me what I wanted to study and he was very suspicious of me because I was this problem child. And I told him I wanted to know why Spinoza was excommunicated from the synagogue, I wanted to know whether German idealist philosophy was linked to the rise of Nazism. And I wanted to understand existential theology - and I was 14 years old.

10:04:31:00

Seq 3 Cours préparation examen JB Berkeley

Now... Okay, that's from my point of view. You could come back with another point of view. But that would be one way of answering the question. You would have to go into both texts and find the relevant passages. And that's your job. And that's something we're hoping you're able to do now by virtue of having passed through this course in the way that you have.

If you want to say, "I find myself moved by what Rousseau says," that's great, then you have to say why. So... "I'm moved because..., I'm persuaded because look at the way this is laid out." "Because when I read this, this is what happens, and this is what convinces me, and this is the figure through which it works and that figure works in the following way." And then I'm moved too. Show me so I can be moved like you.

10:05:21:14

Seq 4 Berkeley

ext campus chorale déguisée, No Pants Day

chanson:

If this was the Judgement Day,

Then every soul would pray.

Every soul would pray.

chanson:

One of these mornings,

You're gonna rise up singin'

And you'll spread your wings

And you'll take to the sky...

Happy No Pants Day!

butler et jacqueline rose parlent aux étudiants:

- You need to leave right now, because you're gonna be on television, and you're gonna be in trouble.

- I'm old enough to be on television without pants on.

(butler)

- C'est la folie de Berkeley, sans culottes, les nouveaux sans culottes, pas révolutionnaires.

- A demain”

et s’éloignent

10:07:04:05

Seq 5 Paris Sciences Po

Sexuality is particularly interesting here because we might think that to be a certain gender is to have a certain sexuality, and that these two are linked in some way; but of course we know that they are not linked. You can certainly be a woman and be heterosexual, bisexual, lesbian or no sexuality at all. Oui, c’est possible. C’est finalement peut être raisonnable.

It is, it is a problem for our gender; it makes us anxious about our gender So, for instance, I have friends who say, ‘I would rather die than wear a dress.’ Some of them are men, some of them are women. 'I would rather die than wear pants.' ‘I would rather die than wear pants. I would rather die’.

One says that one plays with gender. On joue, on joue la femme. On joue, on joue l’homme. I would say yes, it’s true on joue, but it’s not always a simple question of jouissance. It’s also a question of jouissance very often. I love my pants, I love my...I love my shoes, I love my dress. C’est une jouissance très forte, très, très, très magnifique. But sometimes also it is an anxiety, an anxiety, une angoisse, a fear, une peur, a fear of loss, a loss of place, a loss of identity. Right. So even when we have our identity and we play our identity, ça c’est mon identité, je joue mon identité etcetera, somewhere I know that it is possible to lose the identity. C’est possible de perdre une identité. C’est toujours possible, c’est toujours possible.

10:09:45:16

Seq 6 ITV JB Berkeley

Archives famille butler

My mother's family owned movie theatres in the city of Cleveland. And like many Jews they entered into a new industry that started up in the twentieth century.

Archives famille butler

I think I grew up with a generation of American Jews who understood that assimilation meant conforming to certain gender norms that were presented in the Hollywood movies.

Archives famille butler

So my grandmother slowly but surely became Helen Hayes. And my mother slowly but surely became, kinda Joan Crawford. And my grandfather, I think maybe he was Clark Gable or Omar Sharif or something like this. So I grew up with these people who were Jews, they belonged to the Jewish community but they were also Americans and they were both leading their community lives but very much wanting entrance into American society.

Archives famille butler

So I think that by the time I grew up in the late 60s and early 70s looking around me, trying to make sense of gender, I saw these extremely exaggerated notions of what gender was. But I think that these were notions of Hollywood gender that came through Jewish assimilation. And maybe Gender Trouble is actually a theory that emerges from my effort to make sense of how my family embodied those Hollywood norms and how they also didn't. They tried to embody them and then there was some way in which they couldn't possibly and maybe my conclusion was that anybody that strives to embody them also perhaps fails in some ways that are more interesting than... than their successes.

10:12:15:06

Séquence 7, Paris, musée du Jeu de Paume, relevé

Dialogue Judith Butler/Isabell Lorey

IL – Das ist eine Opferrepräsentation...

JB – Das ist kein Opfer. Ich glaub das ist kein… bloß (Lust?) Opfer. Das ist… das ist etwas anderes. In dieser Instanz würde ich sagen, es gibt so… Fürcht…

IL – Furcht!

JB – Ja bestimmt, Fürcht!

IL – Ja, ja…

JB – Aber sie ist… aber sie ist… aber sie lebt noch!

IL – Ja!

JB – Sie ist auch… sehr lebendig!

IL – Und sie kann handeln.

JB – Ja. Vielleicht. Aber, und ich glaube, dass wir sehen hier… diese… sie denkt an etwas anderes. Immer noch! Und es gibt auch so eine Sinnlichkeit, Furcht, vielleicht, vielleicht auch ein bisschen Hoffnung… Hoffnung… Erwartung…

IL – Das Licht ist… ein bisschen hoffnungsvoll, hm?

JB – Ja!

IL – Kann sein.

JB – Ja, kann sein. Sie ist verletzbar. Aber das bedeutet nicht, dass sie verletzt wird. Ja, genau. Es gibt eine sehr wichtige Unterscheidung.

IL – Ganz genau.

JB – Und ich glaube, das ist sehr wichtig, die Verletzbarkeit der Frauen darzustellen. Das ist wichtig für den Feminismus. Das ist nicht gegen den Feminismus. Das ist kein feministisches Problem. Das ist…

IL – Aber viele können es nur lesen als Opfer.

JB – Opfer? Warum?

IL – Das ist auch eine lange Geschichte im Feminismus, hat es ist dieser Opferdiskurs.

JB – Aber sie spielt auch ein bisschen mit diesem Stereotyp, glaube ich.

IL – Ja.

JB – Und das Licht ist auch unheimlich nett, finde ich.

IL –Ja. Aber kannst du dich erinnern, als "Gender Trouble" ins Deutsche übersetzt wurde, bist du auch konfrontiert worden mit so einer Opferposition… also mit einer… aus einer… von... na ja, von sogenannten "Old-school"-Feministinnen, die da immer wieder hinein gefallen sind, in diesen Opferdiskurs.

JB – Ja.

IL – Oder, hattest du den Eindruck?

JB – Ja, ich hatte den Eindruck. Aber damals hatten einige Feministinnen gedacht, dass wir die Frauen immer als Opfer euh…

IL - …beschreiben?

JB - …beschreiben müssen, oder auffassen müssen?

IL – Ja.

JB – Und meine... ich habe betont immer Handlungsfähigkeit.

IL – Ja.

JB – Und das war vielleicht kontrovers, aber die Sherman, hier, ich glaube, das ist so eine Frage von Lüste, von Lust…

IL – von Lust?

JB – Ja. Das ist ein Photo von Lust. Und man könnte sagen… so, in den Vereinigten Staaten, die mit Kindern und anderes, würden sagen, das ist vielleicht eine Art von Pornograph…

IL – Pornographie?

JB – Ja. Aber ich glaube, das ist keine Pornographie.

Il – Eben!

JB – Man kann zugleich… ja, sie kann zugleich zerbrechlich und…

IL - …begehren?

JB – Begehrensvoll?

IL - …begehrensvoll sein.

JB – …begehrensvoll sein.

IL – Begehrenswert.

JB – Begehrenswert, ja?

IL – Ja.

JB – Und das bedeutet, dass wir so einen anderen Rahmen(difficilement audible) haben. Das ist nicht eine pornographische Vorstellung, nach meiner Meinung.

10:16:21:16

Seq 8 ITV JB Berkeley

It was by accident that one of my friends said to me in graduate school: why don't you come give a talk on feminist theory? I said, well... I had read feminist theory, I had read Simone de Beauvoir, it was very important, I had read Gloria Steinem, I had great respect for her - she also loved philosophy. And... And I was very involved in feminist debates, so I would read popular feminist books. And I wasn't sure what to say since it was the first time I was asked to say something in an academic feminist context. So I went back to Beauvoir, Le deuxième sexe, and there I found this one passage which is, of course, perhaps the most famous passage from Beauvoir ,where she says that: "One does not... one is not born a woman, but rather becomes one." And I wrote a... I wrote something about this problem of becoming, and I wanted to know, does one actually ever become one, or is it that to be a woman is a mode of becoming without end, a mode of becoming that doesn't end, that has no end or goal. And then I thought well maybe, you could say the same of gender more generally, that one is not born a man, but rather becomes one, or perhaps one is born male or female, but becomes something which is neither a man nor a woman. And it seemed to me that this notion of becoming - devenir - could lead to any number of directions. So I started, I suppose, to formulate a thesis that would later become the central argument of Gender Trouble.

Photos Cindy Sherman N et B

10:19:06:21

Seq 9 Paris librairie Violette and co

rencontre Butler + Feher avec le public

Butler, to camera:

- Il est toujours là.

(int) Femme, T-shirt "Von Butch"

- Catherine? Ton invitée... Catherine...

- C'est moi qui vais animer ce soir.

- Christine, elle est là-bas.

- (montrant le T-shirt) Je l'ai mis exprès pour vous.

- Bon, on va monter...

Donc "Défaire le genre" réuni en un recueil des conférences et des articles publiés entre 1999 et 2003 sur la question du genre et de la séxualité. Vous expliquez dans l'introduction que votre pensée a été influencée par le développement ces dernières années des "new gender politics" c'est à dire des nouvelles politiques du genre qui sont une combinaison de mouvements concernés par le trans-genre, la transsexualité, l'intersexualité et leur relation complexe au féminisme et à la théorie queer

- C'est difficile de penser quand il fait chaud.

- Je vous traduis pas.

I must say that in my view gender is always a failure. But everyone fails and it's a very good thing that we fail. Because I think that stereotypes are not just images we have of gender but they are we might say an accumulated of facts of social relations that have become naturalized over time.

So for instance if we think of an image of hyper-masculinity and we say "Oh, this is a stereotype!" or we say "Its a norm of some kind", it seems to me that implicitely we are talking about relations between masculinity and femininity, masculinity femininity, male bodies female bodies and how these have become configured over time.

Par exemple lorsque nous imaginons, nous pensons à un stéréotype d'hyper-masculinité il ne s'agit pas simplement d'une pure image d'hyper-masculinité mais véritablement d'un effet, d'un certain rapport social entre masculinité et féminité voire entre corps féminin corps masculin et que ces rapports complexes et cet aspect relationnel en plus s'est non seulement naturalisé mais s'est naturalisé avec le temps, de là le caractère historique de la ???

-

- Je voudrais poser une question sur votre critique de l'idéalisation du trans-gender.

(Butler)

Oh... well, you know... I think it could also be said that transsexuality is a legal category, that there were no transsexuals before there was the legal category for transsexuality. It seems we have to look at what is made medically, technologically possible to understand transsexuality. It seems to me we have to look at what is culturally, artistically made possible to a diverse number of representations and artistic practices, that all of these modes have to be understood as part of what produces our various transgendered and transsexual modes of life.

10:23:09:12

Seq 10 Paris, Musée du Jeu de Paume

Butler seule devant les photos de Sherman (“ les vieilles ”)

10:23:33:24

Seq 11 ITV JB Berkeley

What I worry about is... are the situations in which gender as a norm is exercised coercively. That is to say... There's a story that came out around, I don't know, 8 years ago, of a young man who lived in Maine and he walked down the street of his small town where he had lived his entire life. And he walks with what we call a swish, the kind of... his hips move back and forth in a "feminine" way.

And as he grew older, 14, 15, 16, that swish, that walk became more pronounced, okay... and it was more dramatically feminine and he started to be harassed by the boys in the town. And soon two or three boys stopped his walk and they fought with him and they ended up throwing him over a bridge and they killed him. So then we have to ask why would someone be killed for the way they walk? Why would that walk be so upsetting to those other boys that they would feel that they must negate this person, they must expunge the trace of this person, they must stop that walk, no matter what. They must... they must... eradicate the possibility of that person ever walking again.

It seems to me that we are talking about an extremely deep panic or fear, an anxiety that pertains to gender norms, and if someone says "you must comply with the norm of masculinity, otherwise you will die," or "I kill you now, because you do not comply," then we have to start to question what the relation is between complying with gender and coercion.

10:25:50:15

Séquence 12, Paris, musée du Jeu de Paume, relevé

Dialogue JB/IL (24 40)

JB – Ich hatte das Gefühl, dass ich… ein bisschen… dass ich brauchte eine Befreiung. Eine Emanzipation. Der hat so eine ganz bestimmte Idee von mir, und das hat mit Subversion zu tun, oder mit…

IL – Ein Bedürfnis nach Subversion…

JB – Ja, genau! Ja. Bin ich ein Philosoph? Ja, in einer Hinsicht, aber nicht konventionell…

IL – Hmm

JB – Bin ich eine Feministin? Ja, bestimmt. Es gibt keine Frage… darüber. Ich bin eine Feministin, aber bin ich… bin ich auch queer? You know… Ja, bin ich! bin ich! bin ich! Aber… die Presse hat mich immer… die hat immer so sehr

persönliche Fragen an mir…

IL – Meinst du die ganze Zeit seit 93, oder meinst du jetzt… nach dem Adorno… nach den Adorno-Vorlesungen?

JB – Nach den Adorno-Vorlesungen auch!

IL – Immer noch die persönlichen Fragen…

JB – Ja!

IL – …nach Eindeutigkeit.

JB – Und wie ich auch sehr…

IL – Auch da Kommentare?

JB – Ja. Es gab immer Kommentare.

IL – Es hat sich nicht geändert? In Deutschland? Also, in diesen 7 Jahren, ja? Als du anfingst, die Rezeption… euh… wo nicht, wo die erste… der erste Zeitungsartikel sagte: "Sie hat eine männliche Erscheinung… vielleicht italienischer Abstammung"… erinnerst du dich, ja?

JB – Genau! Genau! Genau! Ich erinnere mich daran.

IL – Ja. Und so ging es weiter. Also dieser…

JB – Das ging ein bisschen weiter…

IL – Ja.

JB – Und weil ich über… über den Körper geschrieben habe, dann erwartet man, dass ich, in meinem eigenen Körper darstellen würde meine Theorie, aber…

IL - …dass du deine Theorie verkörperst.

JB – Aber das tue ich nicht. Das hat mich wirklich verletzt, als die Barbara Duden gesagt hat, dass ich… entkörper… entkörpere… wie sagt man?

IL – Du entkörperst… sie hat dir vorgeworfen, dass du die Frauen entkörperst und dass… sie spricht… sie sprach von dir, oder ja… deinem Text als Frau ohne Unterleib. "Woman without a body." Ja?

JB – Aber das stimmt nicht!

IL – "She constructed a Monster!"

JB – Ja, genau!

IL – Ja.

JB – Ja, genau. Wie manche Leute, ich habe viel… ich habe mich interessiert an Travestis, an Drag Queens, an die Leute die mit Geschlechtsnormen wirklich spielen kann. Aber ich bin nicht so eine Person!

IL – Diese Angst vor Kritik, oder das ist…

JB – Ja.

IL – so parallel…

JB – Ja, ja, genau. So einerseits… einerseits… so…

10:29:16:08

Seq 13 ITV JB Berkeley

I've never found a place, I don't think I'll ever find a place. You know, there are many people who argue that we should all have a place, a gendered place, that we should feel at home in our bodies or at one with ourselves. This, maybe, is a possibility for others. I don't think so. I think...

If my thinking about this is productive at all - it's for others to judge - it's because I... I'm always slightly dis-identified from any given position. I don't belong well in any established category But I'm not also somebody who happily transcends them all. I'm not in favor of happy transcendence. For me gender is a field of ambivalence.

10:30:17:00

Seq 14 Paris Café Beaubourg rencontre avec Tim Madesclaire (journal illico)

(ext)

Hi... Thank you.

Hi.

I'm Tim

Hi, Tim.

I hope you know that you're... you met my friends Okay.

Bonjour, comment ça va ? Très bien ?

Tim : Pourquoi est-ce que vous avez rassemblé tous ces textes-là qui couvrent une période assez large, en fait, sous le titre Undoing Gender ?

JB : I think that another way of naming Gender Trouble would be “ doing gender ”. Right? Gender Trouble was taken as a text that described the ways in which people did their gender. It described gender as a kind of doing, so it was all about acting, doing, making, becoming… What various ways can we do our gender ? What are the various things we can do with gender ? And I think maybe in this text, Défaire le genre, I’m asking a different question which is, first of all, how do the norms that constitute gender, do us and undo us ? That is to say, they make us but they also prevent us from making what we would of ourselves…

On the other hand, it seems to me... we don’t want to say oh, we never want to be undone again, we only want to do ourselves. That’s to privilege a certain idea of self-making that I'm also criticizing. We are inevitably undone by other people, we become undone in our relation with others, we... We don’t always know ourselves, we learn something new about ourselves, we have certain conceptions of ourselves challenged in the course of our relationships, and this kind of

challenge that comes from the Other, we have to be open to this.

Well, if we knew always what we would become, then we would be finished, we would be dead, we would be over…

But I think that part of what it means to be a self is to be open to a future that one cannot know. And it’s to be open to a future of oneself, like what will the self be in the future…

But that only, ...that openess only comes about, I think, through the relations with others.

Tim : This year, they have chosen to ??? the Queeruption movement in Tel Aviv...

In Tel Aviv, yes, yes, I did hear...

Tim : What did you think about this initiative.

My question is whether you can have a struggle for... for the rights of sexual minorities in Israel that does not consider and oppose unequivocally and strongly the occupation. Now some people argue, oh, well, if we start talking about the occupation, that will be politically divisive. But the problem is that the occupation is the background for those struggles.

Tim : That's the question they're asking.

JB : They must ask it. They must ask it. And I know many people who have not gone to the Gay Pride marches there, because of that. But I want to know explicitly whether we can look at the problem of rights or of legal entitlements in Israel more profoundly. Who has rights to land? Who has rights to citizenship? Who has rights to freedom of expression? To sexual rights? To rights of partnership? Can we locate the struggle for recognition and rights on the part of sexual minorities in relationship to the disenfranchisement of Palestine? And I think these have to be linked very explicitly and structurally.

Tim : Do you think... What would you think it would change, in those institutions, such as marriage or parentalité, if we had those rights ? Do you think that it would change something to marriage, if gays had marriage, or it would more change something to gays and lesbiens? How Is this going to interfere?

Well, I want to answer your question directly, but I'm tempted to take a small detour…

I think it's extremely important for radical sexual movements to keep in mind that marriage is only one way of organizing sexuality, and organizing kinship, parenté...

And so I think mariage does have to open, I suppose, it has to open to any two people who may want to join in a marriage contract, although I don’t know why it inevitably is two. Why two?

Tim: Why two? It might be one or three... four...

JB : I don’t understand the two. But I gather it just feels too radical, you know, for most people to say more than two, but I don't really understand why two. I think we should ask the question, two, three, whatever, I don’t know.

But I think... I think that marriage does change... I mean, it doesn't always change when it becomes gay, right? You can have very…In fact, sometimes it becomes almost parodically traditional, sometimes there is almost a resurrection of a traditional notion of marriage that no heterosexual is actually living in anymore.

Let’s hope that these are marriages that breathe. Let's hope they're marriages that are more open. Let's hope they're marriages that are part of a broader social fabric and community. Let's hope that these are marriages that can rethink the relationship between personal life and property relations. Like, do you have to have property in common? How do you raise children if you do ?

is it just the two of you ? Can it be more ? Let’s hope that some of the norms that have made marriage into a narrow and restrictive institution can and will change when and if gay people get married…

Photos Wendy Isaac Judith

10:38:20:24

Seq 15 ITV JB Berkeley

I think that... you know, the word homosexuality was a medical word. You know, t was a word... it would be part of a diagnosis. So there was no term... I mean, I knew the word, but it seemed like a word that took place in a hospital setting, when a doctor was diagnosing a patient. It wasn't something you could be, or say you were. But it became clear to me that I loved people. I didn't have a... I didn't have a name. I didn't think of myself as heterosexual or homosexual, but as I became more passionately involved, especially with one or two young women, girls, at the age of 14, it dawned on me, it occurred to me that there was a word for this. But it was actually a sad moment when the word occurred to me. Because when the word lesbian occurred to me- oh, maybe this is lesbian - it was a moment where the social stigma entered into my thinking, and I felt very condemned by the word. And I had fear of the word. Is this what I am? Is this the name of my passion? Will this ... will this condemn me to social exclusion? Will this destroy my passion? So at the beginning, I think, I had to fight the word or I had to struggle with the word in order to continue to feel what I felt, or to maintain my relations. But it was... It was very odd that the word came from elsewhere, and it came... I mean, homosexuality was medical and lesbian was - I had a terrible image of what a lesbian might be and then I thought well, maybe I will become that terrible image. But there was no movement, there was no community, there was no L-word, there was no media that covered these things. There was no... I was 14, I didn't know anyone who was a lesbian except I had heard of Sapho and I understood she had died a very long time ago.

10:40:50:10

Seq 16 Paris librairie Violette and co.

Butler dédicace ses livres

- Merci.

- Thanks a lot. Have a nice day.

- Thank you.

- Thank you. I really appreciate your comments...

- Bonjour. Pour Frédérique.

- Frédérique...

- Désolée, ce n'est pas le dernier, mais c'est celui que je suis en train de lire. Pour Delphine. Ce n'est pas comme Delphy. Delphine, avec un I.

Ext rues Paris avec Michel Feher et Jérôme Vidal

JB: So, I'm gonna miss you guys. I dream about you already. Je rêve tout le temps... Look at them. They're persecutors, it's true. It's a little bit like my mother, or something.

10:42:26:13

Seq 17 Paris Café Beaubourg

Butler et le photographe descendent l’escalier

Séance photo

- On va peut-être aller par là...

- Il y a toujours des contraintes.

- Oui, il y a des contraintes.

- Il faut travailler avec ma personnalité.

- Je vais travailler avec votre personnalité.

- Je suis limitée.

- Non, je ne pense pas.

- Je pense, oui. Je pense oui.

- Je m'étais dit, je voulais changer des photos traditionnelles dans les cafés. Ca vous ennuie de vous asseoir sur la table? Non. Alors, on fait comme ça. Ca vous ennuie de vous rapprocher ? C'est moi qui vais me rapprocher, alors. Je vais me rapprocher de vous, en fait.

Voilà. Voilà, voilà, voilà. Parfait.

10:43:25:02

Seq 18 Café Beaubourg rencontre avec Juliette Cerf (philo mag)

You know, I think that I return to same problems again and again, in different ways and in differents contexts. So, you know, in my dissertation, I wrote on desire and recognition in Hegel. And then I asked that question differently in Gender Trouble. And maybe again, differently, in Undoing Gender.

But I re-pose the questions, I just think them in different contexts. There's a question of grief and mourning, melancholia, in relation to gender, and AIDS... And then I ask it again in relation to the war in Iraq, who we can grieve, who we cannot grieve... what is a grievable life? But for me, the questions become deepened and more complicated as I re-pose them.

But I don't have a system. I don't try to reconcile my various works with each other. It doesn't interest me. I don't think they're contradictory, but I think they are a process. And I'm always starting again with a different issue. But, you know, I mean, gender and sexuality is part of what I do... then there's more political work, on Israel and the war in Iraq, for instance... War photography, Susan Sontag.

But then sometimes I just write on Kafka, or Spinoza, or something that I care about philosophically. But I don't try to reconcile all these things. It's not a system. It's a process, that's on its way.

I’m... I'm thinking about writing something on... 20th-century Jewish criticisms of state violence, and I'm interested in maybe doing something on 20th-century Jewish philosophy and its relationship to the state, to Israel, to the possibility of critique, again, whether there are traditions of critique, of critiquing state violence... that have come out of the Jewish traditions in particular.

And the reason is because... It is very difficult... for Jews to criticise Israel, for fear that they will be seen as... self hating, or that they will open Israel to an anti-semitic attack.

So sometimes... one falls silent, because one fears the consequence of an open criticism.

Seq 19 Paris Musée du Jeu de Paume

Mains pieds reflet butler dans photos Sherman

Seq 20 ITV Butler Bureau Berkeley

10:47:19:04

One issue that became quite central to activists in the 90s and late 80s was whether there was sufficient or adequate public recognition for the deaths by AIDS, the losses by virtue of AIDS... Was there a way to publicly acknowledge those who had died ? Or was there so much shame attached to the disease or perhaps to being gay that it was difficult to avow and to publicly mourn those who died of AIDS during this time?

So, for me, you know, public mourning is not just something that we do because... we have personal needs to grieve - we do have those ,I'm sure - but I think public mourning gives value to lives, brings us into a kind of heightened awareness of the precariousness of lives and the necessity to protect them and perhaps also to understand that that precariousness is shared across national borders. There's no possibility of overcoming our precariousness, there's no possibility of becoming invulnerable, there's no possibility of evading death; you know. It's not gonna happen. It's not gonna happen So to accept, you know, that kind of precariousness, even finitude as a condition of human life is, I think, maybe a different basis for a certain politics. It's the one that the US foreclosed quite quickly - ten days after 9-11. And it's the one that they do not permit by putting a stranglehold on the media so that we can't understand the precariousness of those lives and the value of those lives that we've damaged or destroyed.

So, I don't know... I suppose that's my link. It seems important. It seems that AIDS activism did... make public mourning very public and important. Las Madres in Argentina have done the same; you know, "Where are the disappeared?" It seems crucial ... to make a lot of noise about those who have disappeared... without ... without a trace. It seems important to mark that, to make the trace, to make a sound, to disrupt the public sphere that would... that notion of the public sphere that would ... make certain kinds of images unseeable, make certain kinds of noises inaudible, make certain kinds of word unsayable. That's a censorship that not only restricts what we can know but also... hampers our capacity to understand... who has been lost and... what violence has wrought and what the value of human lives are.

Seq 21 Paris Musée du jeu de Paume

Butler marche devant les photos de Sherman, sort du champ, générique de fin

Distributor: Icarus Films

Length: 52 minutes

Date: 2006

Genre: Expository

Language: English

Grade: 10-12, College, Adult

Color/BW:

Closed Captioning: Available

Interactive Transcript: Available

Existing customers, please log in to view this film.

New to Docuseek? Register to request a quote.

Related Films

Facebook's 'Adorno Changed My Life'

Facebook's 'Adorno Changed My Life'

In the hyper-connected isolation of social networks names become tags,…