The contemporary art world is changing dramatically. How are collectors,…

Views on Vermeer

- Description

- Reviews

- Citation

- Cataloging

- Transcript

Johannes Vermeer died nearly 350 years ago, but his work continues to evoke inspiration and passion.

Shot largely in New York (home to a third of the world's Vermeer paintings) VIEWS ON VERMEER also travels to Holland, France, London and Washington, introducing us to artists, writers and photographers whose lives and work have been touched by the painter from Delft.

Vermeer has long been admired for the sense of peacefulness that infuses his work. Dutch photographer Erwin Olaf says what he has learned about portraiture from Vermeer is that 'nothing really happens.' One woman reads a letter. Another pours milk. Both their actions are captured in a moment of stillness. 'A life is being lived in those paintings-a small moment,' says photographer Joel Meyerowitz. 'That small moment is where Vermeer and photography meet.'

The film highlights artists whose work is directly inspired by Vermeer, and others for whom the connection to the old master is less direct, yet no less vital.

London-based painter Tom Hunter's work depicts friends and neighbors facing eviction from their homes in compositions drawn from Vermeer. Meanwhile, photographers such as Meyerowitz and Philip-Lorca diCorcia draw on Vermeer more indirectly. diCorcia's 'Hustlers' series features male prostitutes posed in tableaus whose lighting and compositions are reminiscent of Vermeer's. And as in Vermeer's work, diCorcia's images 'reveal themselves slowly.'

One of the more striking sequences in the film juxtaposes the work of Girl with a Pearl Earring novelist Tracy Chevalier with that of Steve McCurry-the photographer who shot the famous Afghan girl photo that appeared on the cover of National Geographic. For Chevalier, the Vermeer painting on which she based the book was not simply a portrait; it captured a moment in a relationship. McCurry compares the Afghan girl-seeing a western male for the first time-to the girl with the pearl earring. Each demonstrates a moment when 'the mundane becomes magical.'

Despite the peacefulness of his work, Vermeer lived in a world wracked by violence. Writer Lawrence Weschler ( Vermeer in Bosnia ) notes that the sense of calm in a painting of Vermeer's hometown-where a recent explosion had killed hundreds-is akin to a portrait of post-9/11 Manhattan. The sense of peacefulness filling the work is not simply aesthetic. It is a political statement wrenched from a world at war.

Many of those featured in the film point to the lack of verisimilitude in much of Vermeer's work. Bricks may not really look the way Vermeer paints them. Certain reflections and highlights may be physically impossible. Yet his work captures something fundamental about reality-something beyond the purely physical. We are surrounded by inexpensive digital equipment that offers the illusion of instantly photographing or filming reality. The work of Vermeer and the artists he has influenced is an invitation to the opposite approach. As artist Chuck Close says, 'Vermeer painted the situation of bricks, rather than individual bricks.'

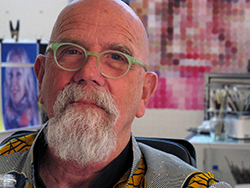

Featuring interviews with painters Tom Hunter, Chuck Close, and Jonathan Janson; photographers Erwin Olaf, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Joel Meyerowitz and Steve McCurry; writers Tracy Chevalier, Lawrence Weschler, and Alain de Botton; architect Philip Steadman; curators Walter Liedtke, and Arthur Wheelock; art historian Geoffrey Batchen, and art dealer Otto Naumann.

'VIEWS ON VERMEER provides thought provoking viewing for both the general and academic audience, and offers a gentle, comfortable 'exercise of the brain' that sparks a desire for more contemplation and discussion.' -Educational Media Reviews Online, February 2012

'Much of the film is quite marvelous: relaxed yet lively, modest but confident. It's like a series of bracing conversations about an endlessly interesting subject.' -Mark Feeney, The Boston Globe

**** 'VIEWS ON VERMEER is a delightful, impressionistic meditation on the many ways the elusive and allusive Vermeer continues to inform, inspire and provoke the contemporary imagination.' -The Globe and Mail

'Required viewing for any Vermeer fan.' -NOW Magazine

'One of the very best [films ever made about art].' -The Star

Citation

Main credits

Pool, Hans (Director)

Pool, Hans (Cinematographer)

Wilt, Koos de (Director)

Lagestee, Martin (Producer)

Other credits

Editor, Maalk Krijgsman.

Distributor subjects

Art; Artists; Painting; Cultural StudiesKeywords

WEBVTT

00:00:30.000 --> 00:00:38.000

[music]

00:01:15.000 --> 00:01:20.000

[sil.]

00:01:25.000 --> 00:01:29.999

Okay. Umm… I think the first time

00:01:30.000 --> 00:01:34.999

I actually saw Vermeer’s work was actually

in a book. Yeah, this is a painting

00:01:35.000 --> 00:01:39.999

that starts through a loaf.

00:01:40.000 --> 00:01:44.999

I mean, look at these people, you get a

glimpse of the dignity, you get a glimpse of

00:01:45.000 --> 00:01:49.999

these peoples importance. Actually you look at

them and feel, wow, these are amazing people.

00:01:50.000 --> 00:01:54.999

I could actually be that person. And

for me, Vermeer was the first person

00:01:55.000 --> 00:01:59.999

who redid that. He pictures ordinary

people, not the Kings, not the Queens,

00:02:00.000 --> 00:02:04.999

not the Jukes, not the Popes,

but the ordinary people.

00:02:05.000 --> 00:02:09.999

Do you mind get it down?

00:02:10.000 --> 00:02:14.999

So this… this actually describes the street

00:02:15.000 --> 00:02:19.999

where I was living for 15 years and

they call it the Ghetto, squatting,

00:02:20.000 --> 00:02:24.999

fly tipping, wish I’d be dead (inaudible) area for

years will be arrested, a blot on the landscape,

00:02:25.000 --> 00:02:29.999

why would people want to live there anyway.

Every painting

00:02:30.000 --> 00:02:34.999

that I found by Vermeer in the books,

I’ll go, well, that looks like,

00:02:35.000 --> 00:02:39.999

Jim or Fred or whoever is

on my street, or Clare or,

00:02:40.000 --> 00:02:44.999

so I would take, I would have the Vermeer book and I’ll

come visit a friend. If I’m going to do this project,

00:02:45.000 --> 00:02:49.999

I want to reshow the dignity of the

people around here, we want to portray

00:02:50.000 --> 00:02:54.999

the beauty of this street and its people.

00:02:55.000 --> 00:03:03.000

[music]

00:03:10.000 --> 00:03:14.999

I suppose the idea came from… from looking at

my local newspaper and in local newspaper,

00:03:15.000 --> 00:03:19.999

it always showed squatters. People living in

abandon houses, in very black and white pictures,

00:03:20.000 --> 00:03:24.999

black and white grainy photograph, always

wilt them bang, evacuated from their houses.

00:03:25.000 --> 00:03:29.999

And every time you look at these pictures and the people,

you thought these are (inaudible) but they’re not like me.

00:03:30.000 --> 00:03:34.999

There are people who don’t care, they are anti-social,

they are drug takers, they are criminals.

00:03:35.000 --> 00:03:39.999

Umm… With my experience,

I was very different.

00:03:40.000 --> 00:03:48.000

[music]

00:03:55.000 --> 00:03:59.999

Felipa, who is a very close friend of mine, she’s living

next door. When we saw this picture, just seem to fit her.

00:04:00.000 --> 00:04:04.999

It’s very beautiful face, very young

at that time. And I used to just spend

00:04:05.000 --> 00:04:09.999

hours having tea at her house. Watching

the light come through her window

00:04:10.000 --> 00:04:14.999

umm… and with this book just thinking… Well,

actually, you know, it’s half past eleven now,

00:04:15.000 --> 00:04:19.999

the light is coming through this window in such

a beautiful way and hitting that back wall,

00:04:20.000 --> 00:04:24.999

is just like this familiar painting.

These are the letters that came for her

00:04:25.000 --> 00:04:29.999

in the post from the High Court, from the

government to, be removed from our houses

00:04:30.000 --> 00:04:34.999

where we were living at that time. I

think I collected from the whole street.

00:04:35.000 --> 00:04:39.999

I think I collected everyone’s letters that

they… they received from the local government.

00:04:40.000 --> 00:04:44.999

And it always be just a Persons Unknown, they

wouldn’t speak to us by name. The only way

00:04:45.000 --> 00:04:49.999

that I thought, we could actually communicate

with them would be, maybe from my art.

00:04:50.000 --> 00:04:58.000

[sil.]

00:05:00.000 --> 00:05:04.999

And then it gets bought by collectors,

it got bought by Sache(ph),

00:05:05.000 --> 00:05:09.999

and then it’s shown in New York, shown

in Holland, and then people see it

00:05:10.000 --> 00:05:14.999

in a very different way. The text is taken out,

so I think some people who saw this picture

00:05:15.000 --> 00:05:19.999

doesn’t even know this about…

about a struggle, really,

00:05:20.000 --> 00:05:24.999

a struggle, in a city, a struggle of people

trying to save their homes and they just see it

00:05:25.000 --> 00:05:29.999

now as a…as a beautiful composition. Which I think

is quite interesting ‘cause now, when you look at

00:05:30.000 --> 00:05:34.999

Vermeer’s painting, people don’t know the whole

story about any of these people in the painting,

00:05:35.000 --> 00:05:40.000

so they make up their own story.

00:05:50.000 --> 00:05:58.000

[music]

00:06:00.000 --> 00:06:04.999

Kind of slurs in, and people who really are very involved

in the arts they know they’re more of Vermeer’s in New York

00:06:05.000 --> 00:06:09.999

than any other place in the

world, tonight it’s one third

00:06:10.000 --> 00:06:14.999

of the artist known production the most.

00:06:15.000 --> 00:06:19.999

He’s… he’s just can’t paint that well.

I mean, he’s not the very best

00:06:20.000 --> 00:06:24.999

handler of shadows, for

instance, and as Rembrandt is,

00:06:25.000 --> 00:06:29.999

by far, he has no emotional context

00:06:30.000 --> 00:06:34.999

whatsoever compared to Rembrandt, not at

all. And he is technically not as good as

00:06:35.000 --> 00:06:39.999

Gerard Dou, Frans I Meiris, Metsu,

a whole host of other artists.

00:06:40.000 --> 00:06:44.999

He’s technically not as proficient.

Meaning, if this

00:06:45.000 --> 00:06:49.999

artist is good as he is, could just give you the

idea of blood rather than exactly, exactly blood.

00:06:50.000 --> 00:06:54.999

You wouldn’t… you wouldn’t be asking

questions like, it looks a little thin

00:06:55.000 --> 00:06:59.999

or it looks like wax is stripping or it

looks like. No Vermeer would show you

00:07:00.000 --> 00:07:04.999

the idea of blood being there. He never did that in

the painting but he certainly would be capable of it.

00:07:05.000 --> 00:07:09.999

And many Old Masters, they leave nothing

to the imagination, Vermeer leaves

00:07:10.000 --> 00:07:14.999

everything to the imagination, in the subject

of his paintings and the way they are painted.

00:07:15.000 --> 00:07:20.000

[music]

00:07:25.000 --> 00:07:33.000

[music]

00:07:50.000 --> 00:07:54.999

You know, I can decode just about

any painting. If I look at it,

00:07:55.000 --> 00:07:59.999

I can figure out how it got made.

But his paintings are

00:08:00.000 --> 00:08:04.999

like they were blown on the canvas,

uh… with the breath of air.

00:08:05.000 --> 00:08:09.999

I mean, it’s just floated on there.

It’s very hard to figure out

00:08:10.000 --> 00:08:14.999

umm… how he did them. And they are

very, very from his contemporaries.

00:08:15.000 --> 00:08:19.999

There was an exhibition at the Met,

called the Vermeer’s contemporaries.

00:08:20.000 --> 00:08:24.999

And in a very large room,

there were comparisons

00:08:25.000 --> 00:08:29.999

between Hawk and Vermeer.

Umm… And from across the room

00:08:30.000 --> 00:08:34.999

uh…the… What they had like

00:08:35.000 --> 00:08:39.999

Vermeer’s little street with red brick

building, next to a similar Hawk.

00:08:40.000 --> 00:08:44.999

And from across the room it looked

like light was coming through it.

00:08:45.000 --> 00:08:49.999

And the Hawk was just paint,

00:08:50.000 --> 00:08:54.999

and Vermeer painted the situation of bricks

00:08:55.000 --> 00:08:59.999

rather than painting

individual bricks. For me,

00:09:00.000 --> 00:09:04.999

umm… he didn’t paint

stuff, he painted light.

00:09:05.000 --> 00:09:09.999

New York city dust, it

doesn’t hurt a painting.

00:09:10.000 --> 00:09:14.999

This is one of a fine Schiller painting.

00:09:15.000 --> 00:09:19.999

A painting that…that, you know, is painted

with this ultra, ultra, ultra touch,

00:09:20.000 --> 00:09:24.999

right? I mean, I find it a bit ugly, there’s no question

about it. Look at the lady’s face, it’s very unpleasant.

00:09:25.000 --> 00:09:29.999

Vermeer will give you a crumpled up carpet

00:09:30.000 --> 00:09:34.999

and but he will never indicate it with

that kind of precision. He didn’t need to.

00:09:35.000 --> 00:09:39.999

He knows that your brain is working

on making that look like a carpet.

00:09:40.000 --> 00:09:48.000

[music]

00:10:25.000 --> 00:10:30.000

[music]

00:10:35.000 --> 00:10:43.000

[music]

00:11:05.000 --> 00:11:10.000

[music]

00:11:30.000 --> 00:11:35.000

[sil.]

00:12:40.000 --> 00:12:45.000

[sil.]

00:13:00.000 --> 00:13:08.000

[sil.]

00:14:30.000 --> 00:14:38.000

[music]

00:14:50.000 --> 00:14:58.000

[music]

00:15:10.000 --> 00:15:18.000

[sil.]

00:15:20.000 --> 00:15:24.999

It’s a series done in Hollywood.

00:15:25.000 --> 00:15:29.999

Subjects were all male prostitutes.

00:15:30.000 --> 00:15:34.999

Uh… I generally pick the

location first and then

00:15:35.000 --> 00:15:39.999

we’d set up lights and situation and

then I would leave my assistant there

00:15:40.000 --> 00:15:44.999

with everything in place and go to the

street where the male prostitutes work.

00:15:45.000 --> 00:15:49.999

And I would ask them

00:15:50.000 --> 00:15:54.999

if they would pose and I would pay them

00:15:55.000 --> 00:15:59.999

and I would bring them there.

And they would almost always

00:16:00.000 --> 00:16:04.999

do the exact same thing

that I had pre arranged.

00:16:05.000 --> 00:16:13.000

[music]

00:16:30.000 --> 00:16:38.000

[music]

00:16:40.000 --> 00:16:44.999

I think there’s something in feeling about voyeurism, which is

also a feeling Vermeer’s work as if… if we are fly on a wall

00:16:45.000 --> 00:16:49.999

and we’re seeing something that we’re normally not ready

to. Almost like a God looking in on this little scene,

00:16:50.000 --> 00:16:54.999

that we’re not, being effect not supposed to be

seen. I think it’s the same in De Corsi’s work,

00:16:55.000 --> 00:16:59.999

as we’re looking into people’s faces who are not aware

we’re looking, we’re not prepared for that look.

00:17:00.000 --> 00:17:08.000

[music]

00:17:15.000 --> 00:17:19.999

This one is more interesting because it’s…

00:17:20.000 --> 00:17:24.999

it’s just not trying so hard.

Reminds me of the way Vermeer

00:17:25.000 --> 00:17:29.999

sets up his foregrounds often with

curtains or tapestries as if we’re

00:17:30.000 --> 00:17:34.999

folding back kind of a stage set to see what’s going

on inside. And even the way that took us here

00:17:35.000 --> 00:17:39.999

is divided of the space here. It’s very

old, very Dutch in a way, at least

00:17:40.000 --> 00:17:44.999

the 17th century pictures and then we have this sort

of sense of divided space, space continuing up,

00:17:45.000 --> 00:17:49.999

for example through the

window, into the world.

00:17:50.000 --> 00:17:54.999

I want that it to be an image

that could be seen to be made by

00:17:55.000 --> 00:17:59.999

a neutral party, someone who’s not

involved in what you are looking at,

00:18:00.000 --> 00:18:04.999

uh… and very often the point of view

00:18:05.000 --> 00:18:09.999

and the camera effects are…are not,

00:18:10.000 --> 00:18:14.999

are something that you would

never do in a…in a snap shot.

00:18:15.000 --> 00:18:19.999

This…this is in some way taken from

a point of view which suggests that

00:18:20.000 --> 00:18:24.999

somebody else is there looking at it.

00:18:25.000 --> 00:18:29.999

The fact that the inside obscures here

00:18:30.000 --> 00:18:34.999

outside is normally

considered to be, I believe

00:18:35.000 --> 00:18:39.999

bad composition, which is

that obscuring the subject.

00:18:40.000 --> 00:18:44.999

So in a way it’s…

00:18:45.000 --> 00:18:49.999

This is a standard theory of architecture

00:18:50.000 --> 00:18:54.999

that complexity and contradiction

have to adjust at the same time.

00:18:55.000 --> 00:18:59.999

And that makes the viewer work more

00:19:00.000 --> 00:19:04.999

and ask more questions and

ultimately it is my ambition

00:19:05.000 --> 00:19:09.999

to have, as I believe, it

was Vermeer’s the secrets

00:19:10.000 --> 00:19:14.999

of the image reveal themselves slowly.

00:19:15.000 --> 00:19:23.000

[music]

00:19:40.000 --> 00:19:48.000

[non-English narration]

00:19:55.000 --> 00:19:59.999

[music]

00:20:00.000 --> 00:20:04.999

I’m an architect and I teach…

I was teaching perspective.

00:20:05.000 --> 00:20:09.999

I have a class in perspective and

I thought what should we do.

00:20:10.000 --> 00:20:14.999

Let’s work perspective backwards,

let’s take some paintings

00:20:15.000 --> 00:20:19.999

and through the natural

images, and reconstruct

00:20:20.000 --> 00:20:24.999

the three dimensional scenes

that they show. And then I

00:20:25.000 --> 00:20:29.999

saw as anyone must see if they look

at all Vermeer’s painting that,

00:20:30.000 --> 00:20:34.999

in his interiors they seem quite a

number, seem to share the same room.

00:20:35.000 --> 00:20:39.999

[sil.]

00:20:40.000 --> 00:20:44.999

If you take a map or

plan of Vermeer’s room.

00:20:45.000 --> 00:20:49.999

If we’re looking from this end,

00:20:50.000 --> 00:20:54.999

we see a blank wall here

in all these pictures

00:20:55.000 --> 00:20:59.999

and the windows are always on the left, and there’s

three of them and equally spaced (inaudible).

00:21:00.000 --> 00:21:04.999

Okay, so the light comes in the left.

00:21:05.000 --> 00:21:09.999

Now, umm… in the reconstructions

00:21:10.000 --> 00:21:14.999

I’ve made of this room, you can find

the…the view points. And they’re always

00:21:15.000 --> 00:21:19.999

about here, they’re not always in quite the same

place. So here’s one. So that’s the position

00:21:20.000 --> 00:21:24.999

from where Vermeer must have

put his eye to get to the

00:21:25.000 --> 00:21:29.999

correct perspective view. It’s what we see

of the room when we look at the painting,

00:21:30.000 --> 00:21:34.999

it’s using a camera, it’s where you put the

lens. And in each… I’ll just draw one.

00:21:35.000 --> 00:21:39.999

In each painting, you

see a kind of pyramid.

00:21:40.000 --> 00:21:44.999

Umm… This is the extent of all

00:21:45.000 --> 00:21:49.999

that you see in the picture.

00:21:50.000 --> 00:21:58.000

[music]

00:22:05.000 --> 00:22:09.999

Now what I discovered is this. If

you take these lines back here

00:22:10.000 --> 00:22:14.999

to the back wall,

00:22:15.000 --> 00:22:19.999

you get a little rectangle. And in

00:22:20.000 --> 00:22:24.999

six cases and perhaps more, this

rectangle is the exact size

00:22:25.000 --> 00:22:29.999

of the painting of Vermeer’s canvas. I

think it must be to do with the fact

00:22:30.000 --> 00:22:34.999

that he’s using the camera, that he

has the camera booth set up here.

00:22:35.000 --> 00:22:39.999

He’s got his lens, he can move the camera

00:22:40.000 --> 00:22:44.999

or the lens about into

slightly different positions.

00:22:45.000 --> 00:22:49.999

The lens is projecting an image on to

the wall, he is tracing it and it is

00:22:50.000 --> 00:22:54.999

for that reason, that it is the

same size as the painting.

00:22:55.000 --> 00:22:59.999

Now here’s my camera,

00:23:00.000 --> 00:23:04.999

and camera obscura means a dark room,

and this is it, it’s just a booth

00:23:05.000 --> 00:23:09.999

and it has… I can put the lens in here.

00:23:10.000 --> 00:23:14.999

This is an old plate camera and

the reason for having that is

00:23:15.000 --> 00:23:19.999

that you can move it back and

forth and focus the lens.

00:23:20.000 --> 00:23:25.000

And it casts an image on to this screen at the back.

Now pull down the, close it to blacken the room.

00:23:35.000 --> 00:23:43.000

[music]

00:23:45.000 --> 00:23:49.999

It has been suggested in the past that

Vermeer’s realism is explained by basically

00:23:50.000 --> 00:23:54.999

copying that projected image. I do think

Vermeer would have been interested

00:23:55.000 --> 00:23:59.999

in the camera and probably knew about it.

Umm… People like Konstantin,

00:24:00.000 --> 00:24:04.999

Helgeson, the Hague, wrote about the camera

00:24:05.000 --> 00:24:09.999

and others were familiar with it. But

for Vermeer, it probably be essentially

00:24:10.000 --> 00:24:14.999

another way of seeing reality, weather

he’s looking at out the window

00:24:15.000 --> 00:24:19.999

or in a camera or seeing a very realistic

effect in another artist’s work.

00:24:20.000 --> 00:24:24.999

He takes that information back

to the studio and he redoes it

00:24:25.000 --> 00:24:29.999

in his own way. Yes, correct.

00:24:30.000 --> 00:24:34.999

Get the telephone bit here. Yes, that’s

good. Yes. That’s right. Very good, Kim.

00:24:35.000 --> 00:24:39.999

One of the problems with being a painter’s

model is, you have to stay still all the time.

00:24:40.000 --> 00:24:44.999

And Vermeer’s models

seem to be in a position

00:24:45.000 --> 00:24:49.999

where they can keep still.

They don’t seem to be holding

00:24:50.000 --> 00:24:54.999

anything up or they simply resting. Can you just

turn your face a little towards the camera?

00:24:55.000 --> 00:24:59.999

There, perfect. (inaudible) a little.

Yeah, middle, that’s great.

00:25:00.000 --> 00:25:04.999

That’s very nice.

00:25:05.000 --> 00:25:09.999

It strikes you immediately once you look

at the camera images like a painting.

00:25:10.000 --> 00:25:14.999

It is… David Hoeppner, who is very

interested in optics and believes that

00:25:15.000 --> 00:25:19.999

painters have used optics over the

centuries. He says to see it is to use it.

00:25:20.000 --> 00:25:24.999

And he means that, it appeals to the

painter’s eye just like a painting

00:25:25.000 --> 00:25:29.999

in some strange way. It’s not because

it’s very detailed. In many ways

00:25:30.000 --> 00:25:34.999

you lose detail. It resolves the

picture into something precise

00:25:35.000 --> 00:25:39.999

but…but vague if you understand me. Something

that is softer than the photograph.

00:25:40.000 --> 00:25:44.999

When you study these light effects

closely you see that many of them

00:25:45.000 --> 00:25:49.999

are very convincing are

in fact not scientific.

00:25:50.000 --> 00:25:54.999

You have the window is opaque,

everywhere except where

00:25:55.000 --> 00:25:59.999

he completes with the hand, the fingers

show through the glass, nothing else does.

00:26:00.000 --> 00:26:04.999

He wants the hand to be complete, but

he doesn’t want any distractions

00:26:05.000 --> 00:26:09.999

out the window. The reflections in the

bottom of the basin of the carpet,

00:26:10.000 --> 00:26:14.999

look like they reflect the carpet directly

00:26:15.000 --> 00:26:19.999

but in fact it’s an invented pattern.

It just has speckles

00:26:20.000 --> 00:26:24.999

of the same color. But I think if you

brought in an optical scientist,

00:26:25.000 --> 00:26:29.999

he would say there’s no

way that would happen.

00:26:30.000 --> 00:26:34.999

There are other features that had to do with,

umm… Vermeer’s treatment of highlights.

00:26:35.000 --> 00:26:39.999

These are the little

reflections, either of the sun

00:26:40.000 --> 00:26:44.999

or of the light coming from windows

that are reflected off shiny surfaces

00:26:45.000 --> 00:26:49.999

like polished wood or metal or glass.

00:26:50.000 --> 00:26:54.999

And they take their shape from the

lights sources that they reflect,

00:26:55.000 --> 00:26:59.999

so that if you are indoors,

they’re usually like a rectangles

00:27:00.000 --> 00:27:04.999

shape of the windows. Vermeer’s

shows them in many cases as

00:27:05.000 --> 00:27:09.999

circles which they’re not.

They would only become circles

00:27:10.000 --> 00:27:14.999

because of the circularity of the lens, the lens

slightly out of focus, turns them into circles,

00:27:15.000 --> 00:27:19.999

circles…circles of confusion.

00:27:20.000 --> 00:27:28.000

[music]

00:27:45.000 --> 00:27:49.999

[sil.]

00:27:50.000 --> 00:27:54.999

When I started as a photographer, I mean,

00:27:55.000 --> 00:27:59.999

I had no photographic examples in mind. I knew… I

knew nothing about photography or any photographers.

00:28:00.000 --> 00:28:04.999

You know, it was… I was

a blank slate, right?

00:28:05.000 --> 00:28:09.999

But I did have an art history background.

So Vermeer certainly

00:28:10.000 --> 00:28:14.999

has always been in my mind since

I was an art student in the 60s.

00:28:15.000 --> 00:28:19.999

Well, so this is

00:28:20.000 --> 00:28:24.999

an 8 x 10 camera, it’s like

a little theatre, you know.

00:28:25.000 --> 00:28:29.999

And it is like a camera

obscura because all it

00:28:30.000 --> 00:28:34.999

is a back plain where the

film goes and a black box

00:28:35.000 --> 00:28:39.999

with the lens on the front, the light comes in and

flips the image upside down. It’s a simple mechanism

00:28:40.000 --> 00:28:44.999

as you can make and it’s basically

the birth of photography.

00:28:45.000 --> 00:28:53.000

[sil.]

00:29:00.000 --> 00:29:04.999

This requires you to go still.

00:29:05.000 --> 00:29:09.999

And to look at something very hard

00:29:10.000 --> 00:29:14.999

and make sure that you mean what you say

with this camera. It’s full of intension.

00:29:15.000 --> 00:29:19.999

And I think that when I

was working on the street

00:29:20.000 --> 00:29:24.999

with this small camera… And here,

I’ll just bring this over here.

00:29:25.000 --> 00:29:29.999

When I was working on the

street with the small camera,

00:29:30.000 --> 00:29:34.999

I was like a jazz musician.

00:29:35.000 --> 00:29:39.999

And when I work with this,

it’s as if I’m Pablo Casals,

00:29:40.000 --> 00:29:44.999

playing the cello. There’s a meditation

on things and Vermeer is about mediation.

00:29:45.000 --> 00:29:49.999

When you look at those paintings,

00:29:50.000 --> 00:29:54.999

when I look at those

paintings, I see the time

00:29:55.000 --> 00:29:59.999

it took to paint them. There’s

nothing hasty about those paintings.

00:30:00.000 --> 00:30:04.999

They seem like they’ve been lovingly made,

00:30:05.000 --> 00:30:09.999

stroke after stroke, they’ve been

brought into the kind of roundness

00:30:10.000 --> 00:30:14.999

that they describe. A life is

being lived in those paintings,

00:30:15.000 --> 00:30:19.999

a small moment, and that

small moment is the place

00:30:20.000 --> 00:30:24.999

where photography and Vermeer connect

because they look like a snap shot

00:30:25.000 --> 00:30:29.999

of a singular moment that is ordinary,

00:30:30.000 --> 00:30:34.999

someone stitching something,

someone reading a letter,

00:30:35.000 --> 00:30:39.999

they are observed moments

that have been stilled.

00:30:40.000 --> 00:30:44.999

So it’s that that’s the appeal of Vermeer.

00:30:45.000 --> 00:30:49.999

[music]

00:30:50.000 --> 00:30:54.999

People always say about Vermeer’s

painting, they’re so still.

00:30:55.000 --> 00:30:59.999

Which at one level’s crazy, of course,

they are still, they are paintings,

00:31:00.000 --> 00:31:04.999

they’re not moving. But it is true they are still

in a way that other paintings are not still.

00:31:05.000 --> 00:31:09.999

And oddly enough this is the flip of

what I was saying. Other paintings are

00:31:10.000 --> 00:31:14.999

still in the way that snap shots are

still, everybody in them is frozen,

00:31:15.000 --> 00:31:19.999

stillness, and frozen are opposite

actually. Stillness implies duration.

00:31:20.000 --> 00:31:24.999

And what Vermeer time and again

does weather here or here,

00:31:25.000 --> 00:31:29.999

or here, or what do we have.

00:31:30.000 --> 00:31:34.999

I think we had up there. I guess I lost her

there, the woman holding the pearl earrings.

00:31:35.000 --> 00:31:39.999

Time and again he chooses to do

00:31:40.000 --> 00:31:44.999

uh… through paintings of woman who are

standing still and having to stand still

00:31:45.000 --> 00:31:49.999

because they are pouring milk, because

00:31:50.000 --> 00:31:54.999

they are adjusting their pearl necklace,

because they’re testing the…the balance.

00:31:55.000 --> 00:31:59.999

Uh… So the time… or because

00:32:00.000 --> 00:32:04.999

they are sleeping in that, in that way

over there. And that… And what you have,

00:32:05.000 --> 00:32:09.999

instead of a snapshot, as you

have the strange feeling of them

00:32:10.000 --> 00:32:15.000

of time passing as you look at them. He anticipates

cinema, which is to say he anticipates duration.

00:32:25.000 --> 00:32:33.000

[music]

00:32:40.000 --> 00:32:44.999

[music]

00:32:45.000 --> 00:32:49.999

I was 19

00:32:50.000 --> 00:32:54.999

and visiting my sister in

Boston on a break from college

00:32:55.000 --> 00:32:59.999

and I went to her apartment and on the wall was

this painting of \"Girl With A Pearl Earrings\"

00:33:00.000 --> 00:33:04.999

a poster of it. And I took one

look, I’d never seen it before

00:33:05.000 --> 00:33:09.999

and I was completely smitten and

it’s been with me ever since.

00:33:10.000 --> 00:33:14.999

Wherever I’ve gone… Even if I’ve gone just

to live abroad for a few months somewhere,

00:33:15.000 --> 00:33:20.000

I’ve taken it with me and it hung in my bedroom

and then later in my study, it’s where it is now.

00:33:25.000 --> 00:33:29.999

I studied art in college

00:33:30.000 --> 00:33:34.999

and there is that strong connection

with, you know, Vermeer and my sort of

00:33:35.000 --> 00:33:39.999

history of art. His quality

of light is something

00:33:40.000 --> 00:33:44.999

which I’ve really studied and had in the

back of my mind. This is the 30x40…

00:33:45.000 --> 00:33:49.999

Yeah, matted yeah. And is this going somewhere or

it’s just on standby? Nope, it was one they got rich

00:33:50.000 --> 00:33:54.999

in him so just… The morning I

photograph the Afghan girl

00:33:55.000 --> 00:33:59.999

in a refugee camp in Pakistan was like

a very ordinary morning. In fact,

00:34:00.000 --> 00:34:04.999

it was around 11 o’clock and the

light was impossible, very bright,

00:34:05.000 --> 00:34:09.999

reflecting off the sand. So I was

actually looking for a place

00:34:10.000 --> 00:34:14.999

to work inside because I knew

the light would be softer

00:34:15.000 --> 00:34:19.999

and I could actually photograph

which, you know, much better effect.

00:34:20.000 --> 00:34:24.999

So as I was walking through this refugee

camp, I heard voices coming from this, uh,

00:34:25.000 --> 00:34:29.999

this tent and it was these young

girls chanting in their classroom.

00:34:30.000 --> 00:34:34.999

So I went up and I went into their

tent and asked the teacher, if I could

00:34:35.000 --> 00:34:39.999

look around and maybe take a few pictures.

I woke up one morning

00:34:40.000 --> 00:34:44.999

and I was lying in bed looking at her and I was sort of fretting

about the book I was working on because it wasn’t going well.

00:34:45.000 --> 00:34:49.999

And I was just looking at

her and I suddenly thought,

00:34:50.000 --> 00:34:54.999

I wonder what Vermeer did to her to

make her look like that? And it was

00:34:55.000 --> 00:34:59.999

umm… suddenly a revelation. Although

I knew a lot about Vermeer,

00:35:00.000 --> 00:35:04.999

I had never really thought about him, except

as the painter. I didn’t think about him

00:35:05.000 --> 00:35:09.999

as a man and it suddenly occurred to me that

this painting was not a portrait of a girl

00:35:10.000 --> 00:35:14.999

but actually a portrait of a relationship, that

what she was looking at, the way she was looking

00:35:15.000 --> 00:35:19.999

was reflecting how she felt about him.

My eye was struck by this

00:35:20.000 --> 00:35:24.999

one particular little girl who had

this really amazing kind of face

00:35:25.000 --> 00:35:29.999

and is really kind of haunted eyes

and I probably had her attention

00:35:30.000 --> 00:35:34.999

for maybe a minute or

two, maybe maximum three,

00:35:35.000 --> 00:35:39.999

and she was kind of looking into my

lens with this kind of curiosity

00:35:40.000 --> 00:35:44.999

or because this was the first time in her

life she had ever been photographed,

00:35:45.000 --> 00:35:49.999

and first time she’d ever met a foreigner.

So in a way she was as fascinated

00:35:50.000 --> 00:35:54.999

with me as I was with her.

What do you want sir,

00:35:55.000 --> 00:35:59.999

I asked, sitting. I was puzzled,

we never sat together. I shivered,

00:36:00.000 --> 00:36:04.999

although it was not cold. Don’t talk. He

opened the shutter, so that the light fell

00:36:05.000 --> 00:36:09.999

directly on my face. Look out of the

window. He sat down in his chair

00:36:10.000 --> 00:36:14.999

by the easel. I gazed at the new

church tower and swallowed.

00:36:15.000 --> 00:36:19.999

I could feel my jaw tightening and

my eyes widening, now look at me.

00:36:20.000 --> 00:36:28.000

[music]

00:36:30.000 --> 00:36:34.999

So she looked into my lens

and beautiful kind of blue,

00:36:35.000 --> 00:36:39.999

green, grey eyes. So you had

this beauty and the sensuality

00:36:40.000 --> 00:36:44.999

but you also had this kind

of raw reality where she’s

00:36:45.000 --> 00:36:49.999

clearly not a model and

she’s clearly not there,

00:36:50.000 --> 00:36:54.999

she’s kind of caught off guard a bit.

And there’s that off guard quality

00:36:55.000 --> 00:36:59.999

to the Girl With A Pearl Earring, her

mouth and her gesture with her head.

00:37:00.000 --> 00:37:04.999

It really makes you feel that

it’s very spontaneous, very real,

00:37:05.000 --> 00:37:09.999

the mundane becomes very

special, and unusual

00:37:10.000 --> 00:37:14.999

and…and magical, taking this kind

of ordinary moment and turning it

00:37:15.000 --> 00:37:19.999

into something really an extraordinary.

He seemed to be waiting for something.

00:37:20.000 --> 00:37:24.999

My face began to strain with the fear

that I was not giving him what he wanted.

00:37:25.000 --> 00:37:29.999

Great, he said softly. It

was all he had to say.

00:37:30.000 --> 00:37:34.999

My eyes filled with tears, I did not shed.

I knew now. Yes, don’t move,

00:37:35.000 --> 00:37:39.999

he was going to paint me.

00:37:40.000 --> 00:37:48.000

[music]

00:38:00.000 --> 00:38:04.999

When the exhibition opened,

Uh… I was driving along here

00:38:05.000 --> 00:38:09.999

and I think where on earth were all these people? Why

are they lining up? And then I finally realized it,

00:38:10.000 --> 00:38:14.999

they were lining up to get into the show.

But over time,

00:38:15.000 --> 00:38:19.999

they realized they need to get here early

and early and so people started lining up

00:38:20.000 --> 00:38:24.999

at 7 o’clock, 6 o’clock, 4

o’clock, 3 o’clock, 2 o’clock,

00:38:25.000 --> 00:38:29.999

midnight, in the middle of winter. So

we were in the snow on either side,

00:38:30.000 --> 00:38:34.999

freezing cold ice conditions. But by the

00:38:35.000 --> 00:38:39.999

end of the show they were

already in line by 9:00pm,

00:38:40.000 --> 00:38:44.999

for entrance the next morning at 10:00am.

00:38:45.000 --> 00:38:53.000

[music]

00:39:05.000 --> 00:39:09.999

I had her on my desk for month. So you

get to know a painting in an amazing way

00:39:10.000 --> 00:39:14.999

in that kind of opportunity. And one of

things that’s so wonderful in this work

00:39:15.000 --> 00:39:19.999

is color. Vermeer is a colorist. We’ll not

think about Vermeer as a colorist so much.

00:39:20.000 --> 00:39:24.999

But if you look at this painting and the red,

that wonderful red hat and the green glaze

00:39:25.000 --> 00:39:29.999

on her forehead, and then the little turquoise

highlight in her eye, and the little pink highlight

00:39:30.000 --> 00:39:34.999

in her mouth, and then the

yellow accents on the blue robe.

00:39:35.000 --> 00:39:40.000

It just, you know, luminous work.

00:39:45.000 --> 00:39:49.999

I never seen Vermeer, I wasn’t aware.

00:39:50.000 --> 00:39:54.999

I knew something about Rembrandt, but I

hadn’t seen Vermeer. And as soon I saw it,

00:39:55.000 --> 00:39:59.999

it was real like an admiration. It was more

like when one falls in love at least sometimes,

00:40:00.000 --> 00:40:04.999

you…you recognize something that I’d lost.

00:40:05.000 --> 00:40:09.999

Vermeer’s paintings are often built up

00:40:10.000 --> 00:40:14.999

very likely. Most of his paintings

took months in order to do.

00:40:15.000 --> 00:40:19.999

There’s a process, there’s building

up forums, building up light.

00:40:20.000 --> 00:40:24.999

Uh… It’s a slow process. But there are

those crucial moments in the painting

00:40:25.000 --> 00:40:29.999

that are not built up,

they’re not a process

00:40:30.000 --> 00:40:34.999

of…of slow working, but they’re,

00:40:35.000 --> 00:40:39.999

last just a few seconds, the

highlights, the girl with

00:40:40.000 --> 00:40:44.999

the red hat, she has turquoise highlights

00:40:45.000 --> 00:40:49.999

on her eyes. The eyes are

not illuminated directly,

00:40:50.000 --> 00:40:54.999

so you cannot really understand

where the light is coming from

00:40:55.000 --> 00:40:59.999

uh… because it doesn’t come directly from where all

the other lights, it’s because they are on the

00:41:00.000 --> 00:41:04.999

other side of the eye. He must have

taken a second a piece just to apply,

00:41:05.000 --> 00:41:09.999

but they make everything, all

the labor that he put in before

00:41:10.000 --> 00:41:14.999

come into focus. They painted turquoise

and it’s just one of those things that

00:41:15.000 --> 00:41:19.999

you don’t conceive. I don’t know

if you could observe turquoise.

00:41:20.000 --> 00:41:24.999

I’ve never seen turquoise highlights

in his dark unilluminated eyes

00:41:25.000 --> 00:41:29.999

but he did the exact sensation

that the… the moistness

00:41:30.000 --> 00:41:34.999

and the tenderness of the eyes. I

always wondered where those two

00:41:35.000 --> 00:41:39.999

turquoise stars have come from.

00:41:40.000 --> 00:41:48.000

[music]

00:42:00.000 --> 00:42:05.000

[music]

00:42:10.000 --> 00:42:14.999

As I said, it’s all been put in here by

my assistants without any sense of order,

00:42:15.000 --> 00:42:19.999

design.

00:42:20.000 --> 00:42:24.999

Oh, one second, here, maybe

I have it in here. Yes!

00:42:25.000 --> 00:42:29.999

Hey, we’re lucky. Look at that, on the top.

And that was a box without a label

00:42:30.000 --> 00:42:34.999

and it was just one of those lucky guesses.

00:42:35.000 --> 00:42:39.999

I have to be careful. This is

00:42:40.000 --> 00:42:44.999

a vintage print.

00:42:45.000 --> 00:42:49.999

So many years ago I had a

studio in Mid Town Manhattan,

00:42:50.000 --> 00:42:54.999

on 19th Street and it faced south.

And I had this incredible view

00:42:55.000 --> 00:42:59.999

of New York City with no big

buildings in front of me.

00:43:00.000 --> 00:43:04.999

Over the years, whenever there was something

interesting, in terms of weather or,

00:43:05.000 --> 00:43:09.999

you know, seasons, or light, I would

make a large format photograph,

00:43:10.000 --> 00:43:14.999

looking south. And, of course,

these two buildings were in,

00:43:15.000 --> 00:43:19.999

they were in the way. But I kept on seeing

00:43:20.000 --> 00:43:24.999

the seasonal changes and

the quality of light

00:43:25.000 --> 00:43:29.999

and how they had sometimes no substance, and

sometimes they were solid, and sometimes

00:43:30.000 --> 00:43:34.999

it was night and they were glowing.

And I kept on thinking of this

00:43:35.000 --> 00:43:39.999

as a landscape, as a mountain

range in the distance.

00:43:40.000 --> 00:43:44.999

And in 2001, I was due to have a show,

00:43:45.000 --> 00:43:49.999

in a gallery in SoHo, called \"Looking

South New York City Landscapes.\"

00:43:50.000 --> 00:43:54.999

It was October of 2001 was the schedule.

00:43:55.000 --> 00:43:59.999

And a few days before September 11th,

00:44:00.000 --> 00:44:04.999

I was Downtown in New York

printing this show and I made

00:44:05.000 --> 00:44:09.999

the last photograph of this place.

This picture was made

00:44:10.000 --> 00:44:14.999

just a

00:44:15.000 --> 00:44:19.999

four days before the Towers were struck. And

I remember, when I made this photograph,

00:44:20.000 --> 00:44:24.999

it was just dusk coming on and I thought,

well, it’s not very interesting,

00:44:25.000 --> 00:44:29.999

no drama or anything. And I thought

I’ll come back in a few weeks

00:44:30.000 --> 00:44:34.999

when I’m back in New York because they’ll always be there.

You know, the way you think something like mountains

00:44:35.000 --> 00:44:39.999

are constant and then, of

course, four days later, gone.

00:44:40.000 --> 00:44:48.000

[music]

00:45:00.000 --> 00:45:04.999

During his lifetime, there were three wars between

England and Holland, one of which resulted

00:45:05.000 --> 00:45:09.999

in Holland losing New Amsterdam.

Louis XIV invades

00:45:10.000 --> 00:45:14.999

Holland and…and the Netherlands breach

their own dykes, resulting in an

00:45:15.000 --> 00:45:19.999

economic calamity which is the mediate,

proximate cause of Vermeer’s own death

00:45:20.000 --> 00:45:24.999

at the age of 43. So his world was

filled with this kind of violence.

00:45:25.000 --> 00:45:33.000

[sil.]

00:45:35.000 --> 00:45:39.999

This of course is the

classic view of Manhattan,

00:45:40.000 --> 00:45:44.999

although it’s also a view of Manhattan with

its teeth knocked out, it’s two front teeth,

00:45:45.000 --> 00:45:49.999

the Twin Towers. Whenever you’re approaching it from

this side, that’s the first thing you think of.

00:45:50.000 --> 00:45:54.999

In much the way that the view have delved,

00:45:55.000 --> 00:45:59.999

the Vermeer, the great Vermeer painting, which to

us is a view of a peaceful town of civic virtue

00:46:00.000 --> 00:46:04.999

and so forth. In fact, at its time,

00:46:05.000 --> 00:46:09.999

was a picture of a town

with its teeth knocked out.

00:46:10.000 --> 00:46:14.999

Armory was right back there. The armory

which is five years earlier had exploded,

00:46:15.000 --> 00:46:19.999

the gun powder had exploded

killing hundreds of people,

00:46:20.000 --> 00:46:24.999

many more in relation to the size of (inaudible)

and were killed in the World Trade Centre

00:46:25.000 --> 00:46:29.999

collapse in relation to the size of

Manhattan. And when you look at, when anybody

00:46:30.000 --> 00:46:34.999

at that time would’ve looked at that painting, that’s what they

would have seen, just as any New Yorker looking at this sight,

00:46:35.000 --> 00:46:39.999

all they can think of is what’s not there.

It’s the thinking of what’s not there.

00:46:40.000 --> 00:46:44.999

With the lamps, as the skyscrapers, something

missing, something terribly missing.

00:46:45.000 --> 00:46:53.000

[music]

00:47:25.000 --> 00:47:29.999

When you see a map on a back wall,

00:47:30.000 --> 00:47:34.999

behind a woman in one of Vermeer’s

paintings, a map is not a neutral option.

00:47:35.000 --> 00:47:39.999

A map is a sight of hundreds of

martyrologies. I mean, this is a place

00:47:40.000 --> 00:47:44.999

where there had been terrible battles between Protestants

and Catholics and the generations immediately prior.

00:47:45.000 --> 00:47:49.999

When you see a woman reading a letter, from who

knows where. When you see a soldier (inaudible)

00:47:50.000 --> 00:47:54.999

with a large hat with a woman.

I mean, all this stuff

00:47:55.000 --> 00:47:59.999

is conspicuously being alluded to. When you see

the lions heads on the chairs, it has this

00:48:00.000 --> 00:48:04.999

continual reference to

a political chaos that

00:48:05.000 --> 00:48:09.999

is conspicuously being pushed

back, held at bay. And in fact,

00:48:10.000 --> 00:48:14.999

what is instead being replaced with is a

peacefulness but a peace that is been invented,

00:48:15.000 --> 00:48:19.999

is been asserted. And one of the things that

draws us so much to Vermeer is…is precisely

00:48:20.000 --> 00:48:24.999

the way that indeed they

are so filled with peace.

00:48:25.000 --> 00:48:29.999

It is peacefulness in this world, as

peacefulness wrenched out of all that, violence

00:48:30.000 --> 00:48:34.999

and violence is what those paintings are about, because

it was conspicuously excluded from those paintings.

00:48:35.000 --> 00:48:43.000

[music]

00:48:50.000 --> 00:48:55.000

[sil.]

00:49:00.000 --> 00:49:04.999

So I think one of the things that Vermeer does

is to challenge our feeling about what’s news,

00:49:05.000 --> 00:49:09.999

umm… and what’s important. So

here we are today, Thursday,

00:49:10.000 --> 00:49:14.999

May the 7th, 2000, and according to the New York

Times, you know, a bomber’s dairy is important,

00:49:15.000 --> 00:49:19.999

budget cuts, et cetera, et cetera.

00:49:20.000 --> 00:49:24.999

So Hollywood’s leading ladies, the problem with Hollywood

leading ladies is that there are not many of them.

00:49:25.000 --> 00:49:29.999

And there are very many of us. So what

happens is, you don’t have one of your own,

00:49:30.000 --> 00:49:34.999

you’re going to end up feeling very sad.

You’re going to think why… why is my life

00:49:35.000 --> 00:49:39.999

not more like this? There’s a lot of envy,

a feeling that the real world is going on

00:49:40.000 --> 00:49:44.999

somewhere else. Look at this, lovely one.

Hilary Swank. So look at her there.

00:49:45.000 --> 00:49:49.999

Would Vermeer have painted her? Probably not.

She looks too confident to openly sexual,

00:49:50.000 --> 00:49:54.999

to openly attractive. She

makes most of us feel,

00:49:55.000 --> 00:49:59.999

\"What’s going wrong in my life?\" How come Hilary

Swank is not in my life? So I think that good thing

00:50:00.000 --> 00:50:04.999

about Vermeer is that he not that. He’s

a opposite of that kind of glamour.

00:50:05.000 --> 00:50:09.999

Umm… It’s not to say his pictures

aren’t beautiful, but I think they are

00:50:10.000 --> 00:50:14.999

idealizations of actually the real world,

our world, not some other fantasy world.

00:50:15.000 --> 00:50:19.999

And so we…we feel grateful

to Vermeer almost for

00:50:20.000 --> 00:50:24.999

saving us from the feelings of

envy and dissatisfaction promoted

00:50:25.000 --> 00:50:29.999

by Vanity Fair.

00:50:30.000 --> 00:50:38.000

[music]

00:50:45.000 --> 00:50:49.999

I think no one is attracted to Vermeer

00:50:50.000 --> 00:50:54.999

who isn’t at some level threatened by

the opposite of the values in Vermeer.

00:50:55.000 --> 00:50:59.999

Uh… I think whenever fall in love

with a work of art, at some level

00:51:00.000 --> 00:51:04.999

because it has something we don’t have enough

of. And I don’t have enough of the Vermeer

00:51:05.000 --> 00:51:09.999

in my life as it were. I didn’t

have enough of the sense of calm,

00:51:10.000 --> 00:51:14.999

of acceptance of daily life. Umm… Of…

00:51:15.000 --> 00:51:19.999

In a sense the, it’s a kind of

wisdom almost you could say.

00:51:20.000 --> 00:51:24.999

Umm… It’s Vermeer’s propaganda for a

certain way of life, umm… which I think,

00:51:25.000 --> 00:51:30.000

me and the modern world, more generally,

are often in danger of losing sight of.